Data scraping: What it is and how it works

The internet holds an enormous amount of information, and a lot of it is collected automatically. Techniques like data scraping are widely used in business, marketing, and research to pull information from online sources at scale.

The same methods, however, can be pushed too far, especially when they’re used to copy large volumes of personal data or reuse information in ways people didn’t agree to. At that point, scraping can run afoul of a site's terms of service and data protection or privacy laws.

This guide looks at how data scraping works in practice, where it can cross legal or ethical lines, and what you can do to reduce the risk of your data or website being scraped without your consent.

What is data scraping?

Data scraping is a broad term for methods used to collect data from online sources, such as websites, databases, and digital documents. It focuses on extracting specific pieces of information and organizing them into a format that can be stored, analyzed, or reused. Scraping is often one step within wider data-collection or data-harvesting workflows, but it specifically refers to the extraction process itself.

Manual vs. automated scraping and its implications

Scraping can be done manually or automatically. Manual scraping involves a person browsing websites and copying information into documents or spreadsheets. Automated scraping uses specialized tools, bots, or scripts to do the same work at a much higher speed and scale.

Automated scraping tools might analyze how a page is structured to pull out visible content, reuse data exposed through interfaces like APIs, or automate a browser to repeatedly load and read pages at high speed.

While the underlying goal is similar (collecting specific data), automation makes it far easier to gather large volumes of information in a short time. That scale is often what turns a seemingly simple data-collection task into something that may breach website terms of service, strain servers, or violate privacy and data protection rules.

Data scraping vs. web crawling vs. hacking

Data scraping is often mentioned alongside web crawling and hacking, but they work differently and have very different implications.

Web crawling

Web crawling is primarily associated with search engines. Web crawlers (also known as spiders or bots) systematically browse the internet, following hyperlinks to discover and index new and updated web pages.

Their main goal is to create a comprehensive index of the web, allowing users to retrieve information through search queries. This process is generally considered symbiotic and beneficial, helping connect users with website content. Web crawlers typically respect robots.txt files, which are used to tell crawlers what URLs they can access on a website.

Data scraping can use the pages that crawlers discover as a starting point, but it goes a step further by pulling out specific data points (for example, prices or contact details) and storing them elsewhere. That extra step, especially at a large scale or involving personal data, is where legal and ethical questions start to appear.

Hacking

Hacking stands apart as an often unauthorized or illegal activity, involving illicit access to systems, networks, or data protected by security measures. Unlike scraping, which usually targets publicly accessible information, hacking bypasses security controls to reach data that is meant to remain private, often with the goal of stealing confidential information, disrupting services, or otherwise causing harm.

That said, large-scale scraping of personal data can still feel like a breach to users, even if no security controls were technically “broken.” For instance, in 2025, researchers at the University of Vienna discovered a flaw in WhatsApp’s “contact-discovery” mechanism that let them systematically identify around 3.5 billion accounts and collect publicly visible profile data, even though no actual “hack” of encrypted messages occurred. They worked ethically with Meta, which has since addressed the issue.

This aspect is why regulators and courts increasingly look not just at whether scraped data was public, but also at how it was collected and used.

Is data scraping legal?

The legality of data scraping is a complex topic with no single global rule. What might be permissible in one context or jurisdiction could be illegal or a breach of contract in another.

Please note: This information is for general educational purposes and is not legal advice.

When scraping can be allowed

Scraping publicly available, non-personal data is generally considered lower risk as long as it’s carried out in respect of the site's terms of service and doesn’t undermine its business model. For example, researchers, journalists, and businesses often use scraping to collect price comparisons, monitor competitors, track online services, or study public online conversations.

There are also industry groups, such as the Ethical Web Data Collection Initiative and the Alliance for Responsible Data Collection, that aim to establish transparent and ethical frameworks for web data collection.

Where legal risks come in

Even if the data is public, scraping isn’t automatically free to use however you like. Here are the main legal issues:

- Data protection and privacy laws: If the scraping involves personal data, it must comply with privacy laws like the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) or U. K. data protection laws.

- Copyright infringement: Data scraping can infringe copyrights if you extract and reuse copyrighted material in unauthorized ways.

- Terms of service violations: Some websites have terms of service that explicitly prohibit scraping. Ignoring those terms can lead to breach-of-contract claims.

- Database rights: In the EU, databases can have a special legal protection if they require substantial investment to create. Scraping large portions of such a database can infringe these rights, especially if it threatens the site’s business model.

- Computer misuse: Accessing data in ways that violate a site’s technical barriers or terms could fall under cybercrime laws. For example, overloading a website with scraping requests can mimic a denial-of-service (DoS) attack, potentially triggering criminal liability.

- Accessing protected data: Web scraping becomes illegal if it involves circumventing security measures, exploiting vulnerabilities, or accessing data that is not publicly available, such as requiring a login.

How businesses use data scraping today

Ethical and legal data scraping can serve numerous legitimate purposes across business, research, and regulatory contexts. The examples below involve data collection practices that respect legal boundaries and terms of service.

Price comparison and aggregation

Price comparison platforms collect publicly available pricing data from multiple retailers and service providers so people can compare options more easily. Responsible providers follow website terms of service, comply with data protection rules such as the GDPR, avoid placing excessive load on sites, and obtain the necessary permissions or consent where required.

However, if scraping expands beyond prices into user reviews, profiles, or other identifiable details, it can quickly move from neutral comparison into large-scale profiling that users never explicitly agreed to.

Market research and trend analysis

Market research often uses publicly available data to spot emerging trends, understand consumer preferences, and track market dynamics. Doing this responsibly means respecting website terms of service, clearly identifying automated tools with an accurate user agent string, and following each site’s robots.txt instructions on what can and cannot be accessed.

The risk arises when data is tied back to individual users or combined with other sources to build detailed behavioral profiles. Even if each piece of data looked harmless in isolation, the combined dataset can reveal far more about people than they expect.

Brand monitoring and sentiment analysis

Brand monitoring tools can track mentions across the web and use AI and natural language processing to analyze sentiment in online reviews, posts, and other public conversations.

When handled carefully, this helps companies respond to service issues and refine products based on feedback that people have chosen to share. Misused, the same techniques can be repurposed to track individuals across platforms, identify vulnerable groups, or target people with highly personalized marketing or political messaging.

The key is to rely on tools that focus on publicly available content, respect user privacy, and follow platform rules.

Can data scraping harm website owners?

While data scraping offers value to those collecting data, it can also create real challenges for the websites being scraped. These include:

- Server strain and performance impact: Since data scraping bots send an excessive number of requests repeatedly to a website’s server, the additional load can slow down websites. The unnecessary load also has the potential to cause temporary outages, significantly disrupting the user experience. Additionally, the worsened user experience can have a negative impact on the reputation of the website’s brand.

- Increased costs: The increased strain that data scraping bots put on websites consumes significant bandwidth, potentially leading to increased hosting costs.

- Intellectual property concerns: Data scraping can raise serious intellectual property concerns, particularly regarding copyright and database rights. If a scraper extracts copyrighted content like articles, images, or unique product descriptions and then republishes or uses it without permission, it can constitute copyright infringement.

For sites that handle personal data, abusive scraping doesn’t just affect infrastructure or content ownership; it can also expose visitors to profiling, spam, or fraud if scraped information is combined with other datasets. Users may blame the site for not protecting their information, even when the scraping is done by a third party.

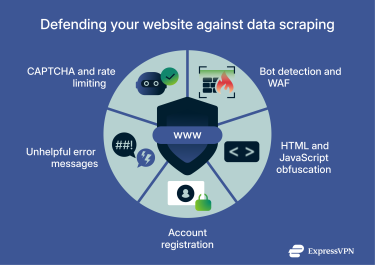

How to protect your website from scraping

Protecting a website and its users from unauthorized data scraping is important for maintaining privacy, security, and control over online content. No single anti-scraping method is perfect, but a layered approach that combines several measures can significantly raise the barrier for scrapers and help safeguard both content and user data.

CAPTCHA and rate limiting

CAPTCHA tests can help filter out basic automated tools by presenting challenges that are straightforward for humans but difficult for simple bots, such as identifying images or solving small puzzles. They are most effective when triggered only in higher-risk situations (for example, unusual traffic patterns or suspiciously high request volumes), so regular visitors aren’t constantly interrupted.

Rate limiting is another key control. By limiting how many requests a single IP address, session, or account can make within a specific time window, you reduce the risk that automated tools can systematically harvest large volumes of data or degrade performance for genuine users.

Bot detection tools and firewalls

Bot detection and management tools can help distinguish between likely human traffic and automated scripts. They typically look at factors like behavior patterns, headers, and device fingerprints to spot and block known malicious bots while allowing legitimate services (for example, reputable search engine crawlers) to continue working.

For example, services like Cloudflare offer bot management features (including Super Bot Fight Mode) that help website owners detect and block scraping or other malicious automated activity.

Web Application Firewalls (WAFs) add another layer of protection by sitting in front of the site and inspecting incoming requests. A well-tuned WAF can block requests that match known attack patterns or scraping behaviors and can also help mitigate a wide range of common web threats, not just scraping.

Obfuscating HTML structure and data delivery

Another set of techniques focuses on making page content harder for scrapers to extract in a straightforward way.

One option is to change how data is delivered. For example, encoding or lightly obfuscating data as it’s sent from the server to the browser can make it more difficult for basic scrapers to understand network responses or figure out how to call API endpoints directly.

Similarly, loading key parts of the page content with JavaScript rather than serving everything as static HTML can interfere with scrapers that rely on simple HTML parsing. Some scrapers can still execute JavaScript, but this extra step increases complexity and may deter more basic tools.

These techniques should be balanced against potential trade-offs, such as added complexity, performance impact, or accessibility concerns.

Require registration for website use

Access policies can complement technical controls. Requiring users to register and sign in to view certain content makes it easier to monitor how that content is accessed. If a pattern suggests that an account is being used primarily for scraping, it’s easier to investigate and, if necessary, restrict or revoke access when activity is tied to a specific profile.

Limit error details when blocking

When a scraper is detected and blocked, it can be helpful to keep error messages generic. Providing too much detail about why a request was blocked can give operators clues about how to adjust their tools and continue scraping.

High-level messaging that confirms the request was denied, without revealing the exact rule or threshold that was triggered, makes it harder to fine-tune scraping behavior around a site’s defenses.

User privacy tools to protect your personal information

While website owners face risks from large-scale scraping, individuals are also affected. Personal data that you post or expose online can still be harvested (sometimes legally, sometimes not) by data brokers, trackers, or malicious actors.

Privacy and security tools can’t stop all data scraping, but they can make it harder for scrapers to silently collect and abuse data about you. They work best alongside good personal data hygiene: limiting what you share, tightening privacy settings, clearing cookies regularly, and reviewing old accounts and apps.

Tools like ad blockers, tracker blockers, and anti-fingerprinting extensions can reduce how much behind-the-scenes tracking happens in your browser. For example, ExpressVPN’s Threat Manager can block known trackers and malicious scripts, adding an extra barrier against invisible data collection. However, it doesn’t guarantee full protection against data scraping. It can’t stop websites from collecting information you provide directly or content you choose to post publicly.

Identity monitoring services such as ExpressVPN’s Identity Defender (available to U.S. customers on select plans) help on the response side. It can warn you if your data appears in dark-web leaks or on data broker sites and it can help you request removals. It’s useful if your data has already been harvested, but it doesn’t prevent scraping or breaches from happening in the first place.

FAQ: Common questions about data scraping

Is data scraping ethical?

Data scraping can be ethical when it aligns with a website’s terms of service, respects user privacy, and takes into account the site’s resources. Factors such as the site’s capacity, privacy expectations, and applicable legal obligations all play a role in determining the ethical considerations around scraping.

Is scraping social media allowed?

It depends on the platform and how the data is accessed. Most major social media sites prohibit automated scraping in their Terms of Service, especially for large-scale or unauthorized data collection. However, some platforms offer official APIs that allow structured access to certain types of data under specified rules and rate limits. It’s best to review each platform’s current rules and rely only on approved tools.

Can I scrape content for academic research?

Scraping content for academic research can be allowed, especially when it involves publicly available, non-personal data and is done for non-commercial purposes, but researchers still need to respect website terms of service and data protection laws, as violating these can lead to legal or ethical issues.

How do companies detect scraping behavior?

Companies can detect scraping by monitoring for unusual traffic patterns, such as high request volumes from the same IP address, abnormal browsing behaviors, or suspicious user-agent strings that indicate automated tools. They often use bot detection systems and firewalls to identify and block scraping attempts while still allowing legitimate users to access the site.

Is it illegal to scrape data?

Data scraping is not inherently illegal. Its legality hinges on several factors: the type of data being scraped (public vs. private), the site’s terms of service, whether security measures are bypassed, and adherence to privacy laws like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Is data scraping GDPR-compliant?

Data scraping can be General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)-compliant, but only if strict conditions are met. Collecting personal data means you must have a clear legal basis, respect individuals’ privacy rights, and follow transparency and security requirements. Even publicly visible personal data is protected under GDPR, so scraping it without consent or proper safeguards can lead to serious compliance issues.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN